The history of Stuart turner.

The following article appeared in the Stuart International Model Engineers Club SIMEC, the home-brew magazine that followed from a newsletter, ran for 51 editions from Spring 1977 - Spring 1990

The following article and associated illustrations have been based on a lecture given in Henley Town Hall in 1972 by Mr. Peter Barnard, Managing Director of Stuart Turner Ltd.-Editor. "The History of Stuart Turner Ltd.”

The name "Stuart" conjures up many different images in people’s minds. Expressions such as "World unique," "Practically an institution,” "Works which seem to have come straight from a Victorian engraving,” are a few of the comments made by past and present customers from all over the world.

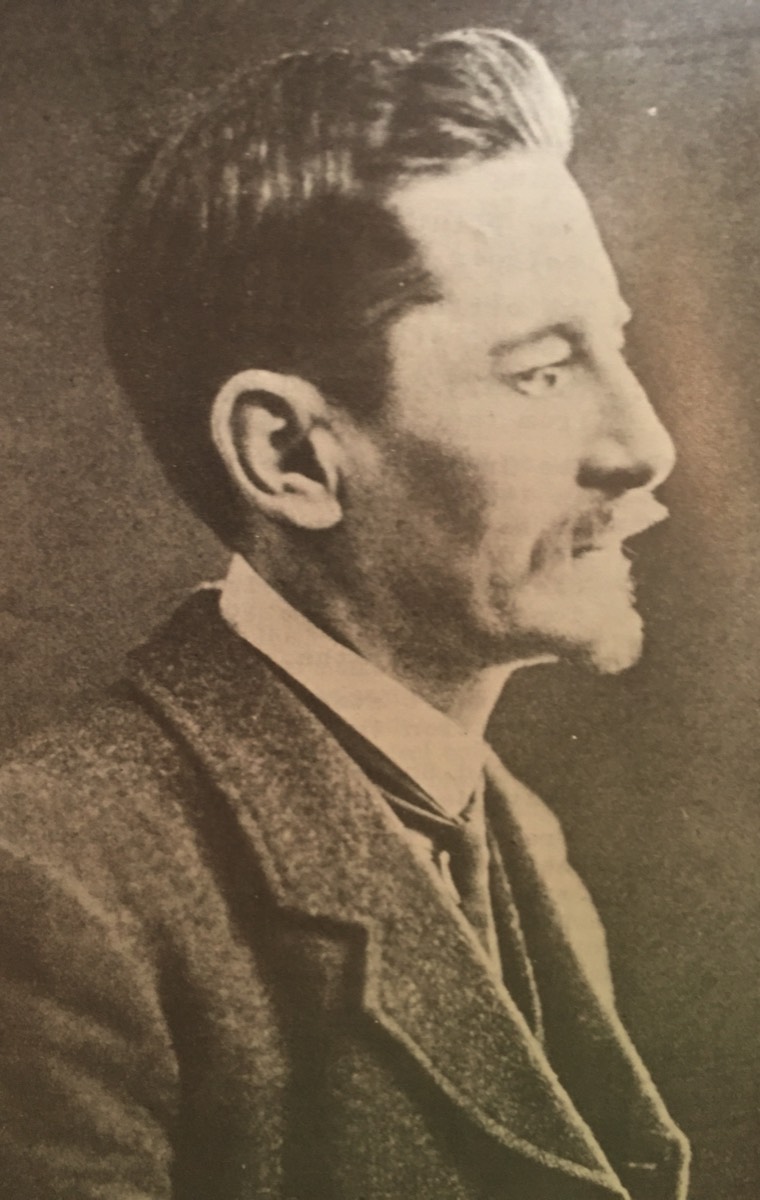

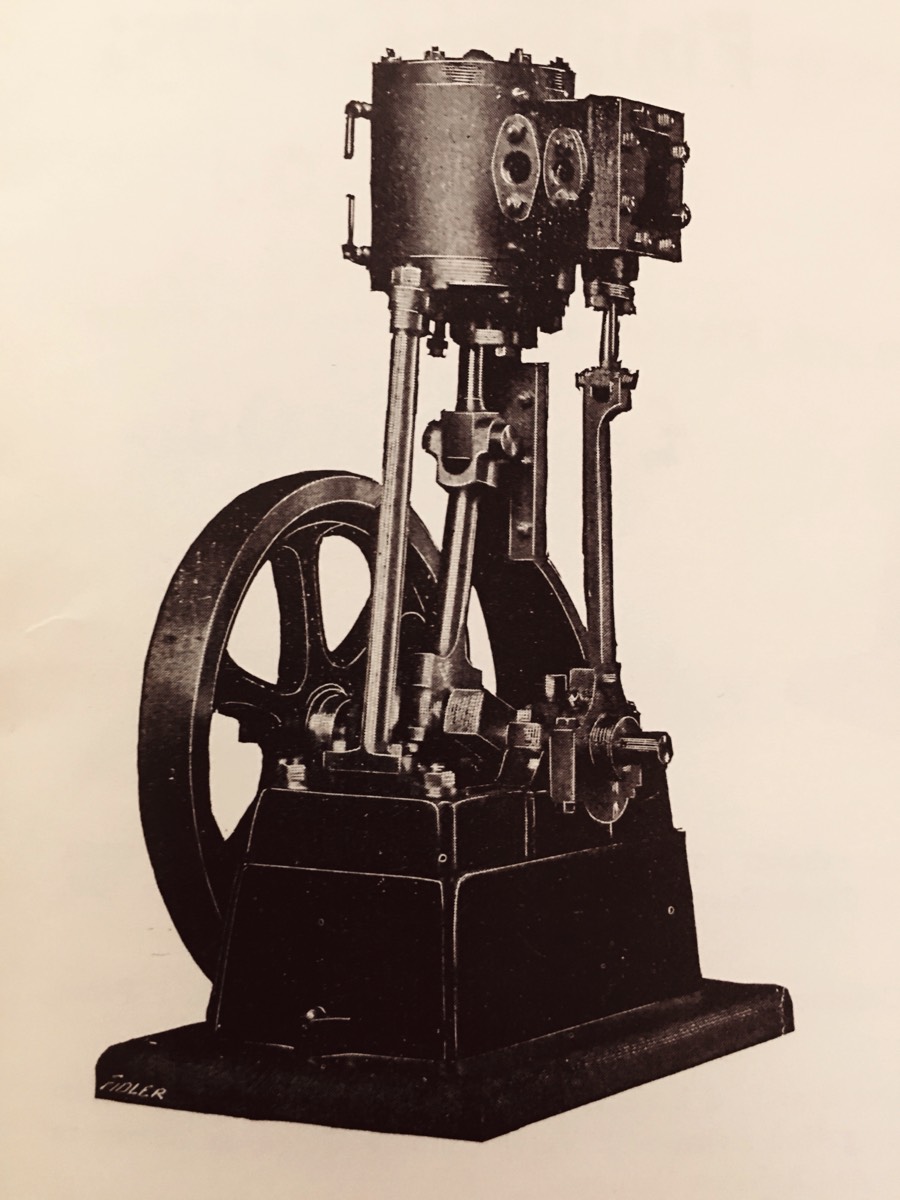

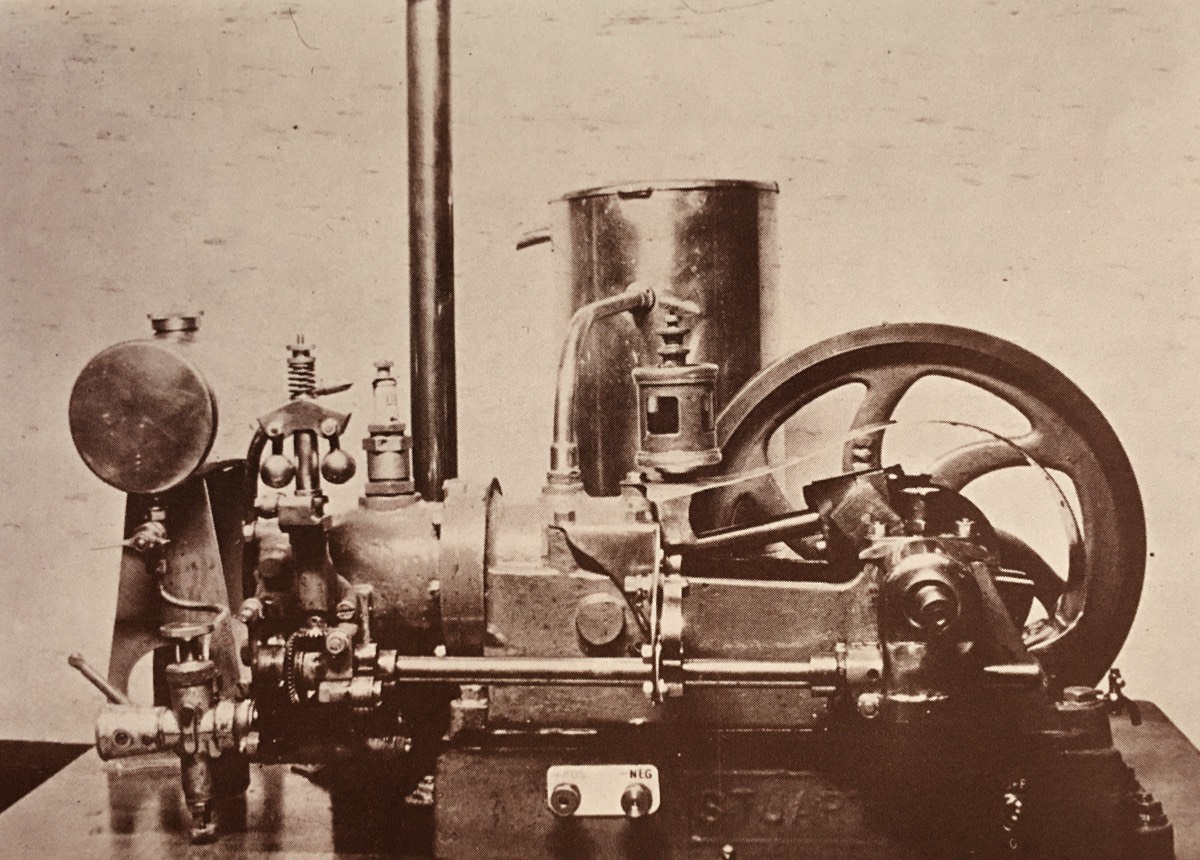

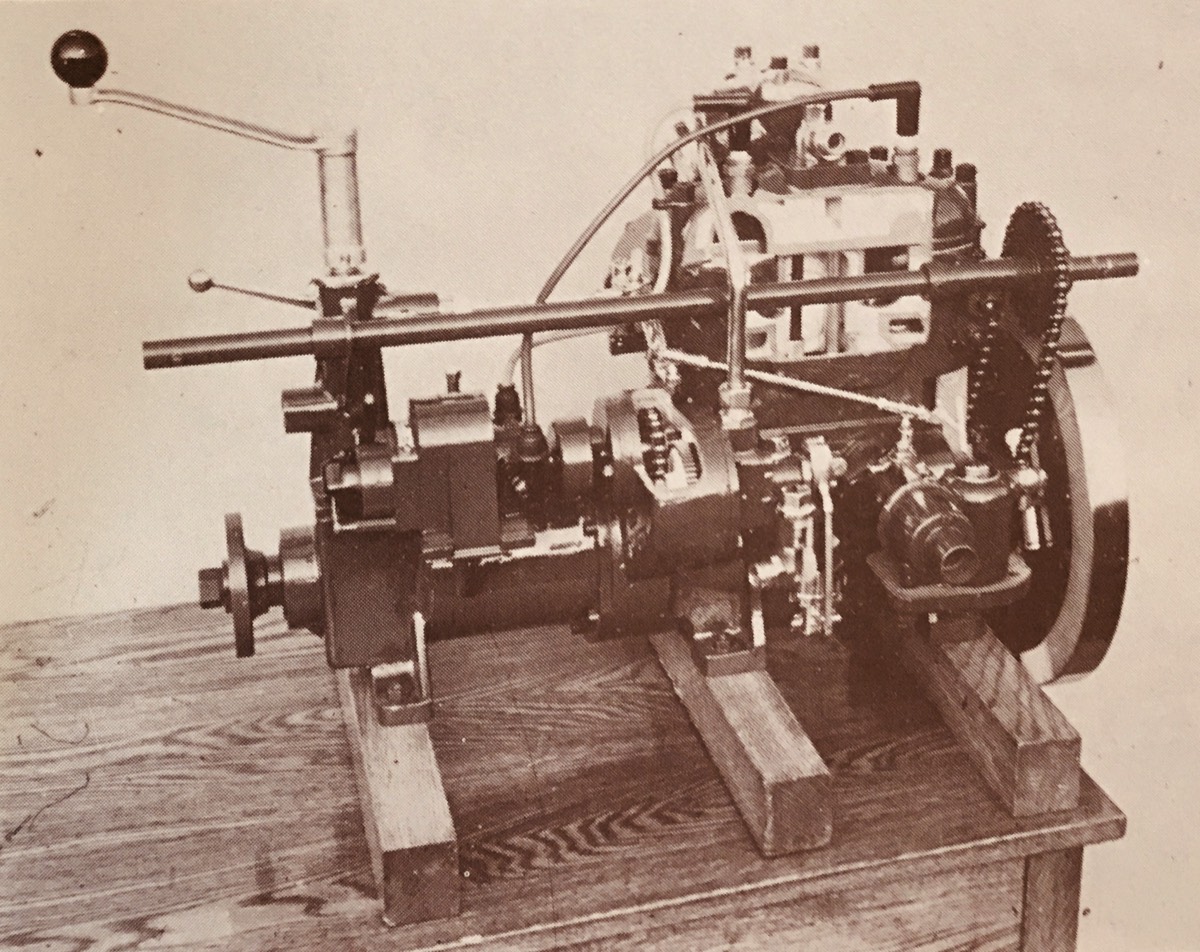

"Stuart" is a Christian name, the man who started it all was Sidney Marmaduke Stuart Turner. (Fig. 1) Comparatively little has come to light concerning his early years but it is known that he started his working life in a bank, this he found uncongenial and soon left. His well-meaning family then got him a position in a customs office but he liked this work even less! He took french leave and joined up with a local millwright, where he got experience in a wide variety of jobs, mending lawn-mowers, tinkering with engines generally and all the other odd jobs that come the way of millwrights. This job only lasted a few months, however, and he travelled to the Clyde, where he served in Alexander Stevens' shipyard for two or three years, as far as records can ascertain. He went to sea with the Clan Line, again for a couple of years, during which time he had the dubious pleasure of reading his own obituary notice when he was wrongly reported as having been drowned at sea. Little more is known of his life in Scotland, but a few years later he turned up in Jersey, where he ran quite a successful business as an electrical engineer. At that time, nearly all electric supplies were run either by private companies or by municipalities. Stuart Turner tried his hand at supplying the island of Jersey with electricity, but he was a far better engineer than he was a businessman and the project failed. Looking for fresh fields to conquer, he eventually arrived at Shiplake, near Henley-on-Thames and got the job of looking after the steam generating plant at Shiplake Court, in those days, electric mains were few and far between and nearly all big houses had their own gas or steam plants. When the B.B.C. occupied Shiplake Court during the Second World War, the foundations of the power plant were still there. While at Shiplake Court, Stuart Turner designed the First of a long series of model steam engines. He also made the patterns which he sent away for casting. He then machined these and built up what is now known as the Stuart No. 1 Engine (Fig. 2) Thls was the very first Stuart design and it has been made with very few modifications, ever since 1901. It features in the current Stuart Catalogue and, so far as is known, has been in every catalogue produced. It is a very fine engine with beautiful lines and is not too difficult to build. He showed this engine at a local exhibition, and then approached Percival Marshall, the then editor of "Model Engineer." At that time the magazine had only been running for a couple of years so they were very keen to encourage anybody who had new ideas, in those days there seemed to be plenty around. Percival Marshall gave Stuart Turner a good write-up in 1901 and after the engines were advertised, the orders came in as fast as he could handle them, these were for the sets of castings which people could then machine for themselves. At that time Stuart Turner was about 33 years old and "Model Engineer" was writing:- 'Stuart engines are now too well known to need lengthy descriptions," this within 13 or 14 months of first publicising them-quite a success story in such a short time.

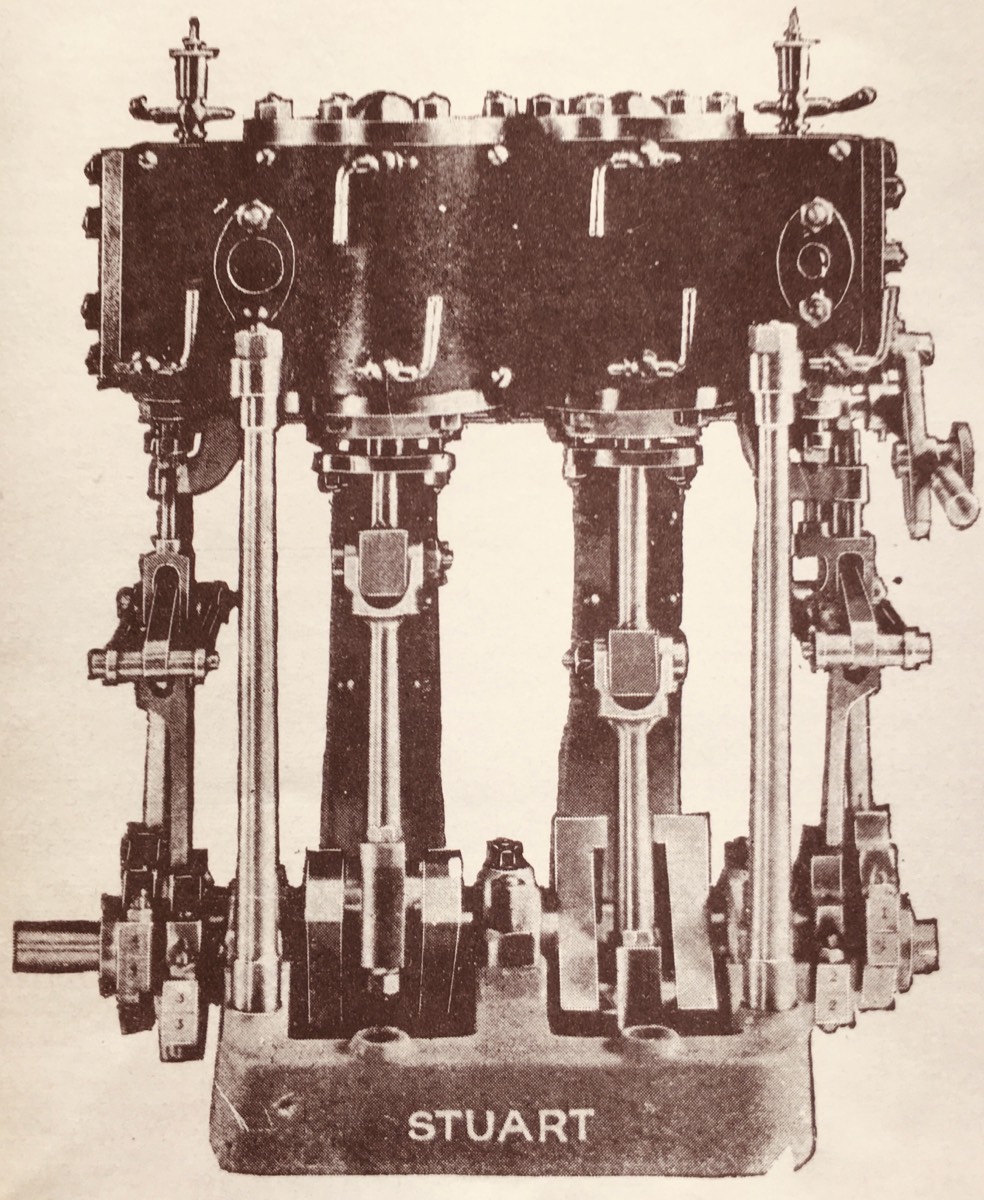

Meanwhile, he continued working at Shiplake Court, his employers must have been fairly easy-going because he probably spent much more time on his models then he ever did in looking after their generating plant. Within a couple years he had designed and marketed three or four more engines, of which the No. 3 Compound is probably the most interesting (Fig. 3) The illustration is taken from the 1905 Catalogue and is the original version of the No. 3 Compound which the company made up to 1928.

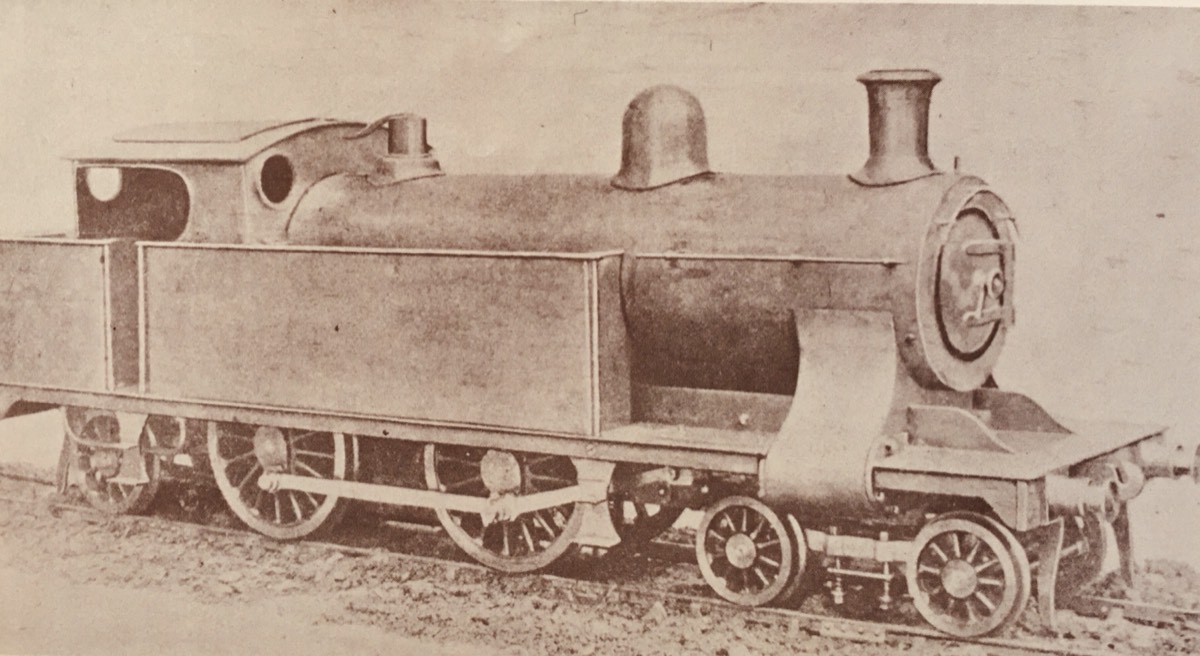

In these early years of this century Stuart Turner had made himself known to the Society of Model Engineers (founded in 1899) and it is certain that the Society's first secretary, Herbert Sanderson, got to know Stuart Turner through their association during the various exhibitions and conversations. Later Herbert Sanderson was made Treasurer and the new secretary was Henry Greenly, in later years, both these men were to be closely associated with the company, Sanderson becoming Managing Director in 1921. Stuart Turner was always "on the ball" and exhibited on every possible occasion, he didn't miss out much on publicity and in the early issues of "Model Engineer" there was nearly always some mention of what Stuarts had or had not done. The engines they were selling were very much in advance of what was then available so there was a ready market for them. Although a number of excellent models were being made, there were few, if any, which were not scaled down versions of full size engines or locomotives. Stuart engines were of very simple design, made specifically for the amateur builder to construct, to demonstrate the principles of steam or to enjoy running for various purposes. However, the company did make one scale model at this time, a Henry Greenly design of an L.N.W.R. locomotive to Erin. scale (Fig. 4) Stuarts got the job of making this engine for a Colonel Harvey, in competition from several other engineers. The contract time was 18 weeks, but Stuarts completed it in 16 weeks, earning a bonus and several compliments from the purchaser for the excellence of the work done. (The facsimile reproduction of the Stuart 1906 Catalogue, gives full details of this engine, as well as copies of Greenfly's original working drawings, end papers). About this time, Stuarts had no fewer than nine engines in their range, mostly vertical designs, but also a couple of horizontal types.

One of the big events in the history of the company occurred in 1903, when Stuart Turner met Alec Plint, the son of an old friend. (Fig. 5) He was an exceptionally gifted engineer and from the First World War until his premature and much lamented death in 1948, designed everything that Stuarts made. This was a tremendous achievement for one man, more especially as he had many other interests. He founded the town library, designed the sewage works and held office twice as Mayor of Henley. His eldest son, Michael, inherited much of his talent and the name lives on in the engineering world as Plint&Partners,Consulting Engineers, of Wokingham.

Another stalwart, W. G. (Jimmy) Ayling, joined the firm in 1905. He had been an apprentice at Wallis & Stevens and had also worked for a car firm who produced a £100 car, when this firm went broke, Ayling came to Stuarts. At First, the actual workshop was behind 26 Duke Street in Tuns Lane, Henley, though there was still another part of the works in Shiplake, some three miles away, at this time.

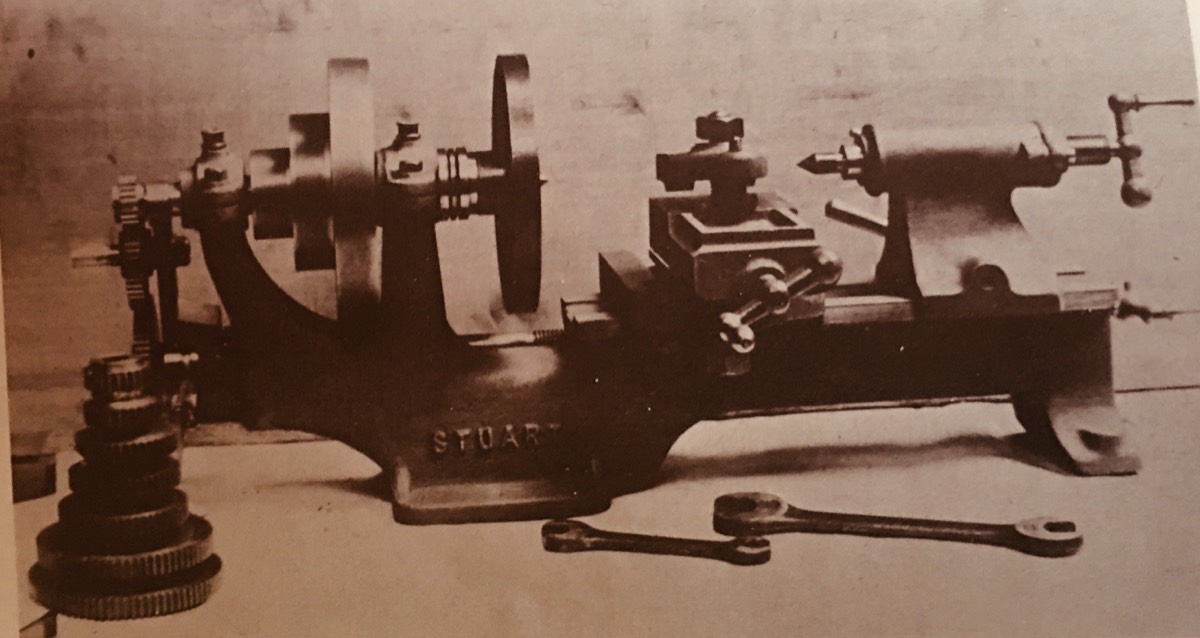

Apart from the basic work on model engines, the company began to make a number of small gas engines which were sold for house generating plants. They were also making model locomotive frames and com- pound engines of various types. In 1907 Stuarts brought out a lathe (Fig. 6) This was marketed at 5 pounds and sold well, no doubt it would have continued to do so had it not been for the arrival of the Drummond lathe which was of comparable quality but which sold. for 5/- less. In addition, various tools, such as surface plates were manufactured by Stuarts, but the model business continued to be of first importance and when the "Model Engineer" magazine held an exhibition, its first, at the Royal Horticultural Hall in London, Stuart Turner was there at Stand No. l, full of models and engines of all kinds. (Fig. 7) shows Stuarts stand in 1909, still No. l, a number the company retained for some years. It will be seen that there were quite a number of wooden boat hulls exhibited on the stand, these were machine carved by a firm run by Henry Greenly. At the 1909 show, the prize for the most interesting trade exhibit went to a rival of Stuarts, Bassett-Lowke. This firm became very famous for their locomotive models, but, Stuarts tended to leave the locomotive trade to Bassett-Lowke from then onwards.

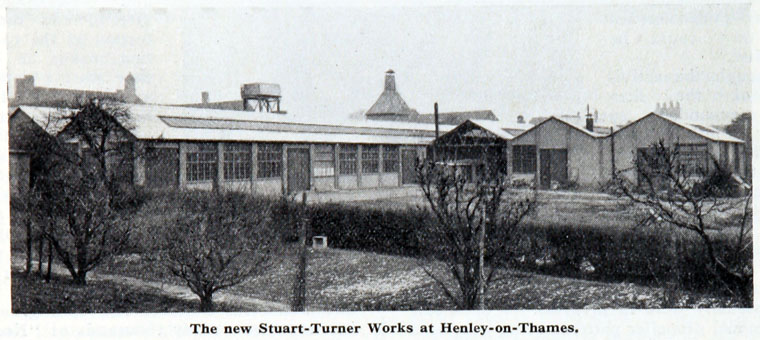

By 1907, Stuart Turner needed more space and premises were leased in Friday Street, Henley, at £15 per annum from a Mr. Chambers. By the following year, despite the three premises in Friday Street, Duke Street and Shiplake, Stuart Turner was obliged to expand still further and leased Nos. 43 and 45, Market Place, Henley, from Mr. Hockley, builder, at a rental of £70 per annum. (Fig. 8) is a photograph of these premises, named Shiplake Works, until recently they were subsequently occupied by Piercy's Dairy. Today, the buildings are the offices of a firm of solicitors, while the entrance to Stuarts Works was that of the Broadgates Inn. Even today, the old. tap room is now the top sales office, dealing with models and electric pump repairs. The other leases were relinquished and Stuart Turner agreed to live rent-free at No. 43 Market Place with a salary of £3 a week. He left his Shiplake job altogether and at the same time bought out Greenfly's company, "The Machine Carved Model Company." Stuart Turner acquired this company for £70 so must have been reasonably flush at the time. Later on, Greenly bought shares in Stuarts. About that time, the company took on its first apprentices, named Courtney and Bailey, they both paid £50 premium for the privilege, it was quite usual at the time to pay a premium to a works of any consequence. Of course, Stuarts still have apprentices but they do not pay premiums! They are, we think, treated quite handsomely and are given day release for further training at the nearby Technical College, just up the road. Stuarts' star apprentice is Tom Barlow, who became Managing Director of Rolls-Royce Heavy Oil Engine Group at Shrewsbury. An apprenticeship at Stuarts tends to give a much wider train- the products of the company have always ing than at many firms as been quite varied.

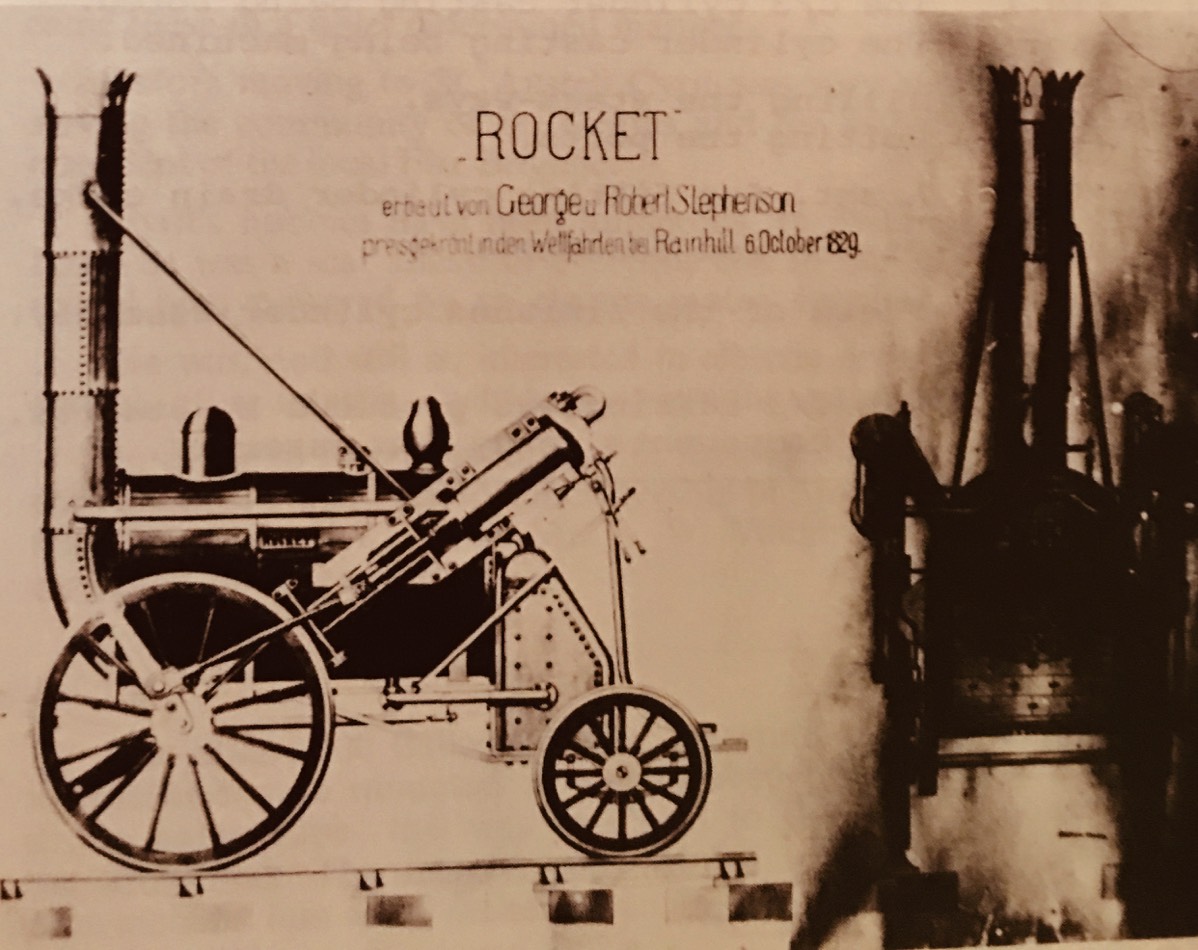

Although we mentioned that Stuart Turner did not make much in the way of scale models, there have been one or two exceptions. (Fig. 9) shows the very fine scale model of Stephenson's "Rocket," to 1/8 scale, done for the Science Museum in London where it can still be seen. Most of the machining was done by Mr. Joe Cossins and the "sectioning" and general erection was done by Mr. Masters, an excellent craftsman , a couple of years later he built a similar one for the Berlin State Museum (Fig. 10)

Meanwhile Stuart Turner continued to diversify and the 1911 catalogue included even punkahs and ceiling fans, apparently these did not sell well as they failed to reappear in later catalogues.

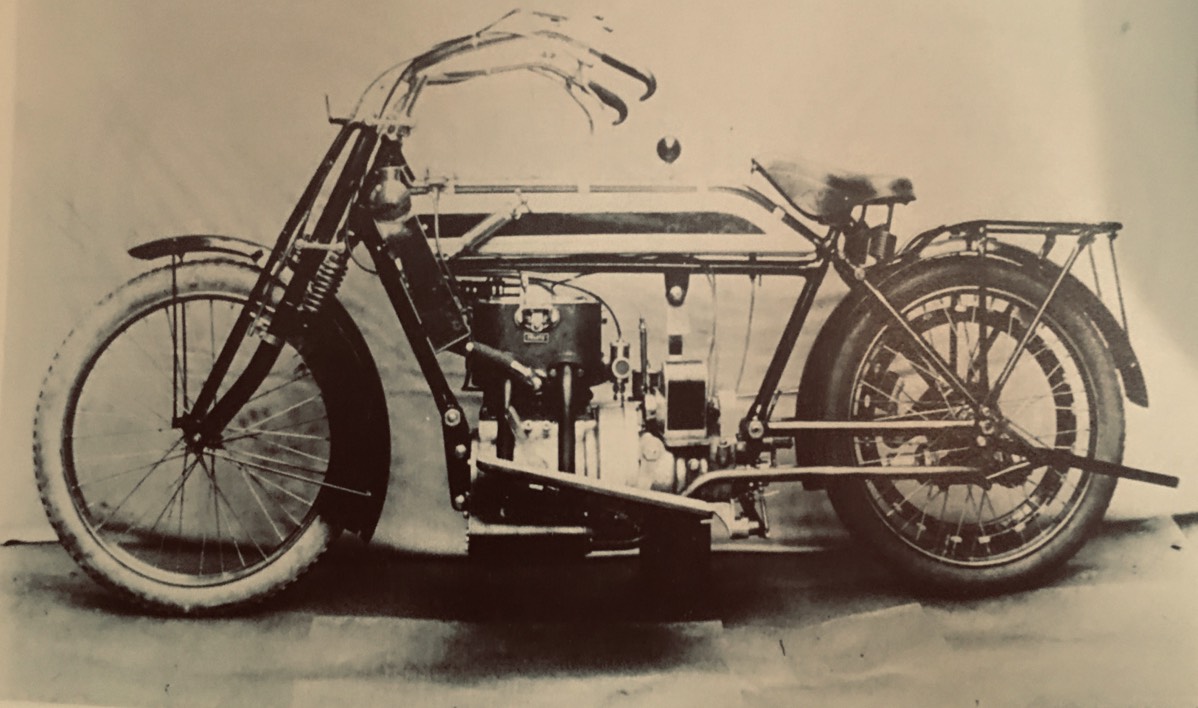

The "Model Engineer" magazine, in its early days very much reflected the history of Stuarts, for instance, since about 1909 it had been featuring notes on motor-cycles. In those days there was a great vogue in do- it- yourself motor-cycles. People could buy the frame and engine separately and make them up into their own design, as a result, there were a great number of interesting varieties. From 1909 onwards Stuarts were experimenting with various engines for motor-cycles and in 1911 they produced the "Stellar" (Fig. 11). This machine was of a very advanced design for that time, with water-cooled twin-cylinder two-stroke engine, shaft drive and worm gear transmission. Only about 13 of these machines were made, one is still at the Stuarts works in Henley, having previously been on loan to the Beaulieu Motor Museum in Hampshire. This particular model has been licensed quite recently and has taken part in a number of veteran and vintage rallies, it should last many more years. In 1912, it was taken on manoeuvres with the Territorial and Regular Army, Winston Churchill was then Minister for War and Jimmy Ayling (Andrew’s elder brother) and Herbert Sanderson covered a lot of ground with the "Stellar." Jimmy left a classic account of those heady days. Following the "Stellar," Stuarts then produced a number of lightweight engines for the Dayton motor-cycle (Fig. 12). It seems probable that these engines were being produced at the rate of 20 a week, so sales must have been quite lively. The Dayton machine went on reliability trials and Alec Plint and Jimmy Ayling entered for a trials course at Sutton Coldfield, it is recorded that the former proved the better rider. Just one week before the First World War broke out, on July 28th, 1914, it was recorded that a Dayton machine climbed Alms Hill, Henley, six times in succession , quite a feat for motor-cycles in those early days.

At this time, the British Imperial Trans- Antarctic Expendition was being assembled and (Fig. 13) shows Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship "Endurance" which actually left England before the outbreak of war. Shackleton did, in fact, offer the use of the ship for the war' effort or to help in any way he could himself, the authorities told him to carry on with his expedition because at that time it was thought that the war would be over in a matter of months. The intention was to cross from a base in the Weddell Sea to McMurdoe Sound, crossing over the South Pole but in January of next year, 1915, the ship was trapped in ice off the Caird Coast and there she was stuck, 200 miles from the nearest land and 1,000 miles from any kind of human assistance. Shackleton and his crew eventually had to abandon the "Endurance," after drifting for five months on pack ice, they reached Elephant Island. The connection with Stuarts in all this is that the "Endurance" was fitted with a Stuart petrol-engined generating set which was presumably used to keep the batteries topped up and for general lighting purposes. The ship had floodlights fitted at the end of her spars, to illuminate the surrounding area of ice while she lay trapped. The plant was left running with these lights on, right up to the moment when the ice crushed the hull and she disappeared from view, the photograph was taken when the expedition members finally left her to her fate.

There is very little information about what went on at Stuarts during the 1914-1918 War, presumably they were so busy making every- thing that nobody had time to keep records. It is fairly certain, however, that the company turned out large quantities of items such as nuts and bolts and there are records of gas valves being manufactured. Round the clock shifts were operated and at one stage some 400 employees were on the books. Both Plint and Sanderson had joined the Army and been posted on service, meanwhile Stuart Turner remained and ran the business with another director, Tommy Nash. The company minutes book records that they often worked eighty hours a week , they were more or less operating on a shoestring budget and lacked capital for expansion. However, at the end of the War, the War Office Trench Warfare Supply Department wrote a very nice letter to congratulate them on the very low percentage of rejections and the high quality of their inspection, which is something that Stuarts have always endeavoured to maintain.

In 1917, the congested conditions at No. 43, Market Place became intolerable and the premises next door, the old "Broadgates" Inn, were purchased from Messrs. Brakspear, the local brewers. By the following year, 1918, they had more than 100 capstan lathes in operation, which Stuart Turner said were all ready for the nut and bolt trade. Unfortunately by the end of the War, there were a great number of other firms also ready for this type of work and the expected business failed to appear, Stuarts machines were all manually controlled then and could not compete with the new automatic machines coming into operation at that time. To put it bluntly, the company was not doing too well. However, in 1919 both Sanderson and Plint had been demobilised and were able to return to work. Plint designed an engine which became the forerunner of all the petrol engines which Stuarts produced during the next 30 years, this was the single cylinder two-stroke P3, to be followed later by the P4, P5 and P6. At this time Bill Perrin, later to become company Chairman, joined the company and the following year, 1920, Plint was made a director, as he had done most of designing of products he was officially put in charge of design. Stuart Turner himself had by now had some differences with other members of the company and went off to South Africa, though many years later he returned to Britain and settled down to Westcliffe-on-Sea, in Essex.

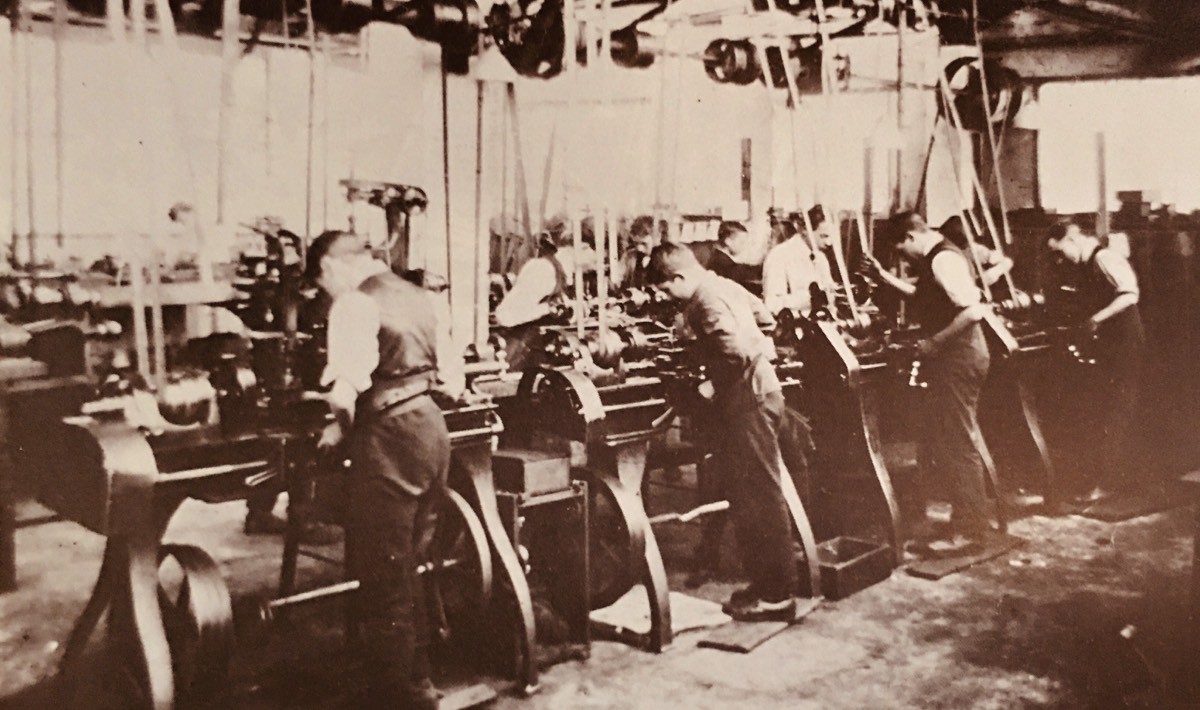

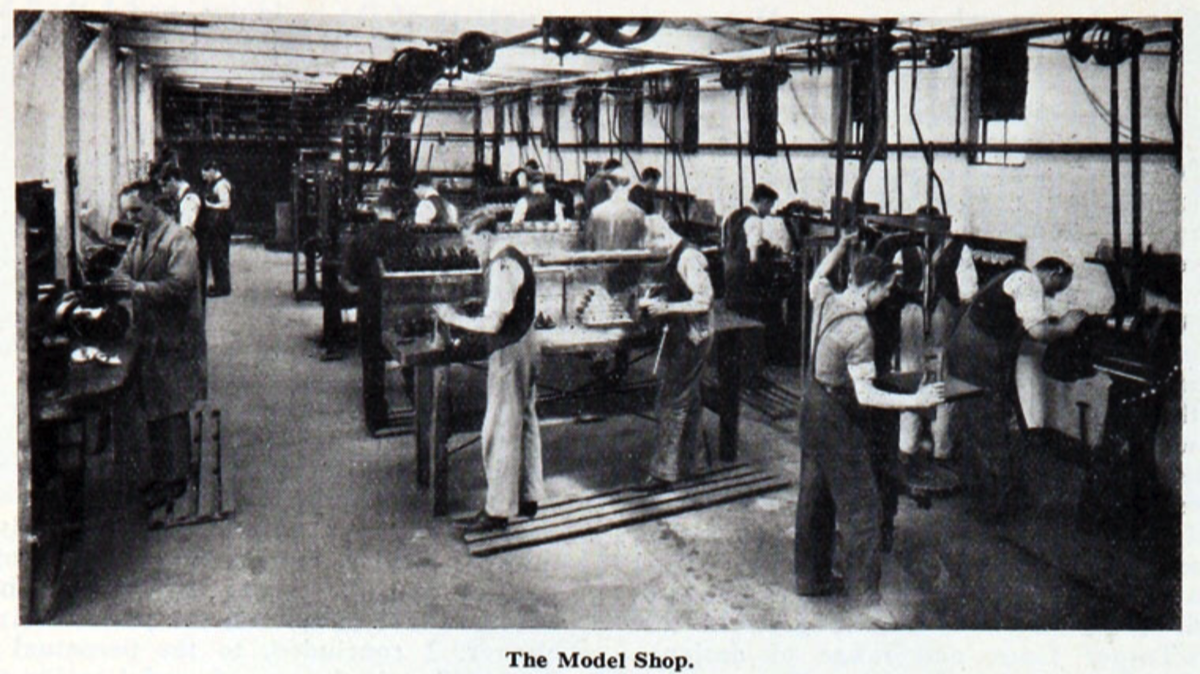

(Fig. 14) shows a view of the model shop in about 1920, some of the lathes were treadle operated. The pattern of work had remained fairly constant till this time, but with the departure of Stuart Turner a number of directors' meetings were held to decide what the future should be. It was planned that Plint should plan an extension of the foundry and that Mr. Nash should endeavour to recruit more female labour for the bolt shop, as well as finding out whether the provision of stools would increase production. One interesting note from the minutes book states that one director should always be present at 8 a.m, this still obtains today.

The next innovation into the Stuart range was in 1920 when the No. 400 gas engine appeared, this was following in 1922 by the No. 600. In 1924 Stuarts secured a contract for supplying the War Office with a number of 400-watt air- cooled generating sets, designed for pack-mule transport, these sets were completely self-contained, weighed 118 lbs. and were designed to work under extreme climatic conditions. (Fig. 15) They were still being made at the beginning of the Second World War and had done service in many parts of the world. The Arab Legion and the Bengal Sappers and Miners were some of the exotic destinations for these sets. Though most went for military use, there were exceptions, for example, in 1933 there were two Everest Expeditions and both used Stuart plants. One set was run at a height of 16,500 feet, possibly still a record height for a stationary engine. An interesting feature of these sets was the use of the metal electron, very expensive but incredibly light, though with. the curious propensity of catching fire if machined too fast!

The other major contract in the 20's was one from the Post Office for petrol-driven charging plants for installation in country telephone exchanges. An operator started the plant up and it then automatically cut out when the batteries were fully charged, these exchanges were usually visited once a week. This contract was "bread and butter” work for Stuarts and it kept them going all through the l 920's and well into the l930's. The last contract from the Post Office was in about 1940 when they ordered 40 3Kva. A.C. standby generators mounted on trailers, these were scattered throughout the country as a safeguard against mains breakdown due to bombing attacks.

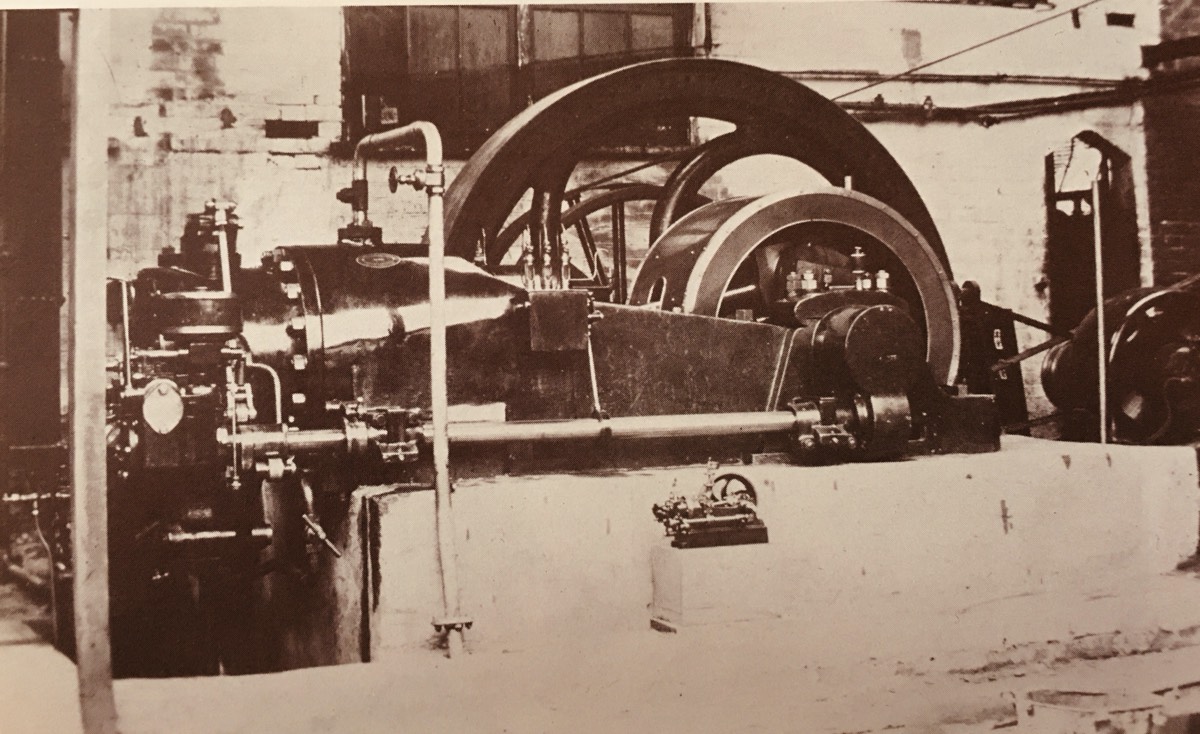

(Fig. 16) shows the 80 h.p. National Diesel engine which was installed at the Henley works sometime during the l920's, alongside it is one of the little model gas engines first made in 1926. Unfortunately the National had to go, the space is now used for brazing and testing model boilers and engines. The Stuart range of model gas engines comprised No. 400, 600 and 800, though popular, their sales were never spectacular. (Fig. 17) shows a No. 800 which was recently found by an employee of the Armstrong-Whitworth Aircraft Company and rebuilt in 1952.

Quite apart from the War Office and Post Office contracts, the 1920’s were a boom period for petrol and gas-driven house lighting plants. There was, at that time, a lot of talk about the wonderful new grid system that was going to transform life in this country, and of course, in some ways, it did, but rather like North Sea Gas, it was going to be very cheap and like North Sea Gas it wasn't! However, as far as the public were concerned, everybody thought about electricity and rushed off to buy their own lighting sets-Stuarts did very well as a result.

In 1928 a new director, Jesse Rymer, joined Stuarts and energetically set about looking for new projects , soon after his arrival a Danish business- man asked if Stuarts could provide engines for a fleet of 50 pleasure boats on a lake in South Wales. (Fig. 18) He wanted the job done in four weeks. Stuarts had never built marine engines before, apart from models, but Alec PIint was quite equal to the occasion and said "Oh, yes." The engines were delivered on time, which was quite an achievement for any firm. In the event, it happened that the engines arrived but some of the boats themselves weren't quite ready. The engines were installed in those that were completed, but the next morning the boats were all under water, the caulking having been skimped! The supplying of these marine engines at very short notice was a good indication of the kind of engineer Alec Plint was, he could tackle a problem and come up with a working design in a matter of hours. He continued to work like this for the rest of his life. At this time he was also working on a diaphragm pulsator system for automatic milking machines. He patented the design and Stuarts made them under licence exclusively for Messrs. Gascoignes of Reading. It was really the foundation of Gascoignes` business from then onwards and was a great advance over anything that had previously been done in the automatic milking of cows.

In 1931, building had been started on the new works premises to the rear of the Broadgates Hotel site and was more or less complete by 1936, when the erection shop buildings were added. It soon occurred to the management that with the success of the 50 marine engines built for the South Wales Fleet, that Stuarts could benefit from this trade, especially as Henley was on the Thames where a large number of pleasure craft were used. Jimmy Ayling's brother, Andrew, who was a born salesman, was encouraged to go round the boatbuilders and interest them in Stuart marine engines. Although at that time boats were usually built to individual requirements, David Hillyard of Littlehampton was persuaded that boats could be built more cheaply to a single design. The cabin fitments could be modified to suit different buyers, but the hull was standard, at that time this was quite a new idea. It certainly simplified matters for Stuarts as Stuart engines were fitted as standard to this type of boat. By the time the Second World War broke out, Stuarts had captured about 75 % of the market for marine engines up to 8 b.h.p. for auxiliaries, launches, yachts' tenders, dinghies, small pleasure boats, etc. (Fig. 19) The pleasure boat business was very good for Stuarts, nearly every resort round the coasts of Britain had a fleet and the engines earned a fine reputation with the hire operators. An offshoot of the boat business was the “dodgem" cars which were fitted with the same marine engine but with radiator cooling. At one stage Stuarts also supplied quite a few electrically driven cars and boats which operated from a trolley-pole contacting an overhead netting.

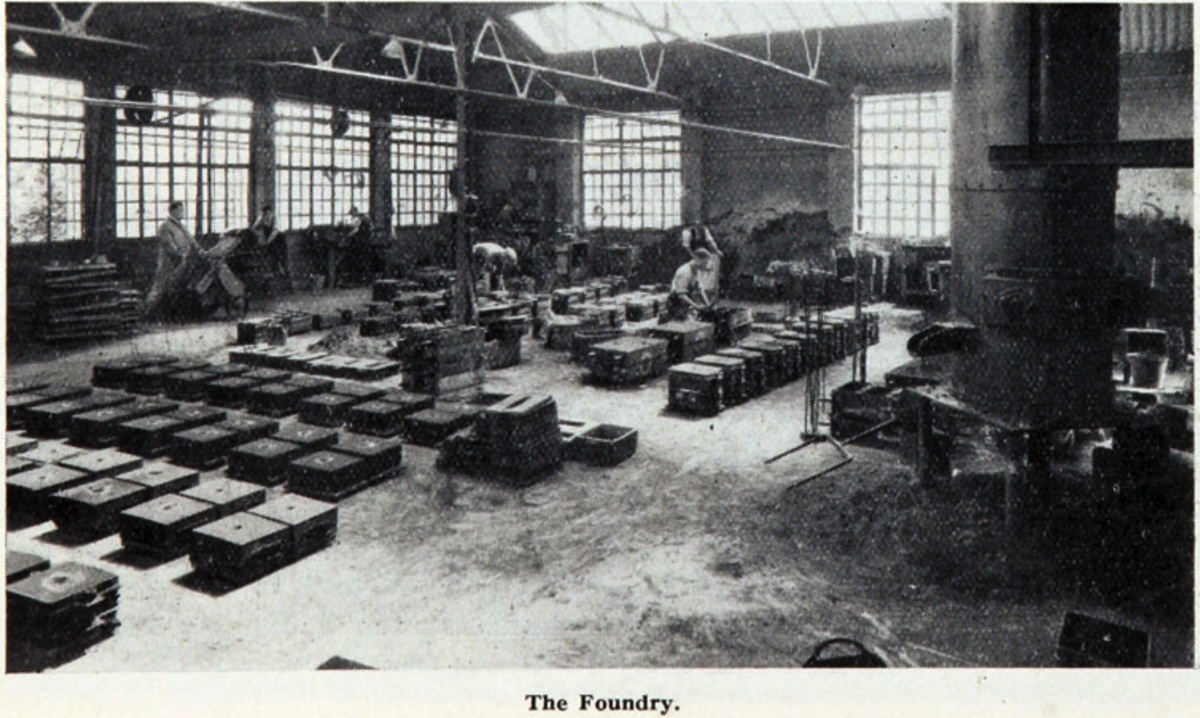

Of course, the heart of the works has always been the foundry, if you have a good casting, you can produce a good product. This is particularly true of model castings, Stuarts have always had a good reputation for the quality of their castings and although there have been times when the firm had endeavoured to obtain castings from outside, they have never measured up to the standard required. Until 1935, Stuarts had not manufactured pumps in a commercial way, although they had made model ones for assembly by customers. However, in this year, Alec Plint had the brilliant idea of evolving a non-leaking frictionless pump gland, he took out a patent on this and since then it has been successfully used by many manufacturers, including the car Industry. The system comprises of a carbon ring rotating on machined metal surface, Preferably cast iron, though nowadays stainless steel brass and manganese are used for certain fluids. The ring is backed by a rubber disc pushed onto the pump spindle which ensures a watertight seal, this gland does not drip and can be left standing indefinitely. This was how Stuarts got into the small pump business. In the first instance Stuart pumps were sold mainly for garden use, for fountains and waterfalls, but soon many industrial uses were found for them. One of the first was for the cooling of gun barrels and Stuarts sold a good many pumps to the War Office as a result. By 1958 the firm was making 20,000 pumps a the figure is more than double this today.

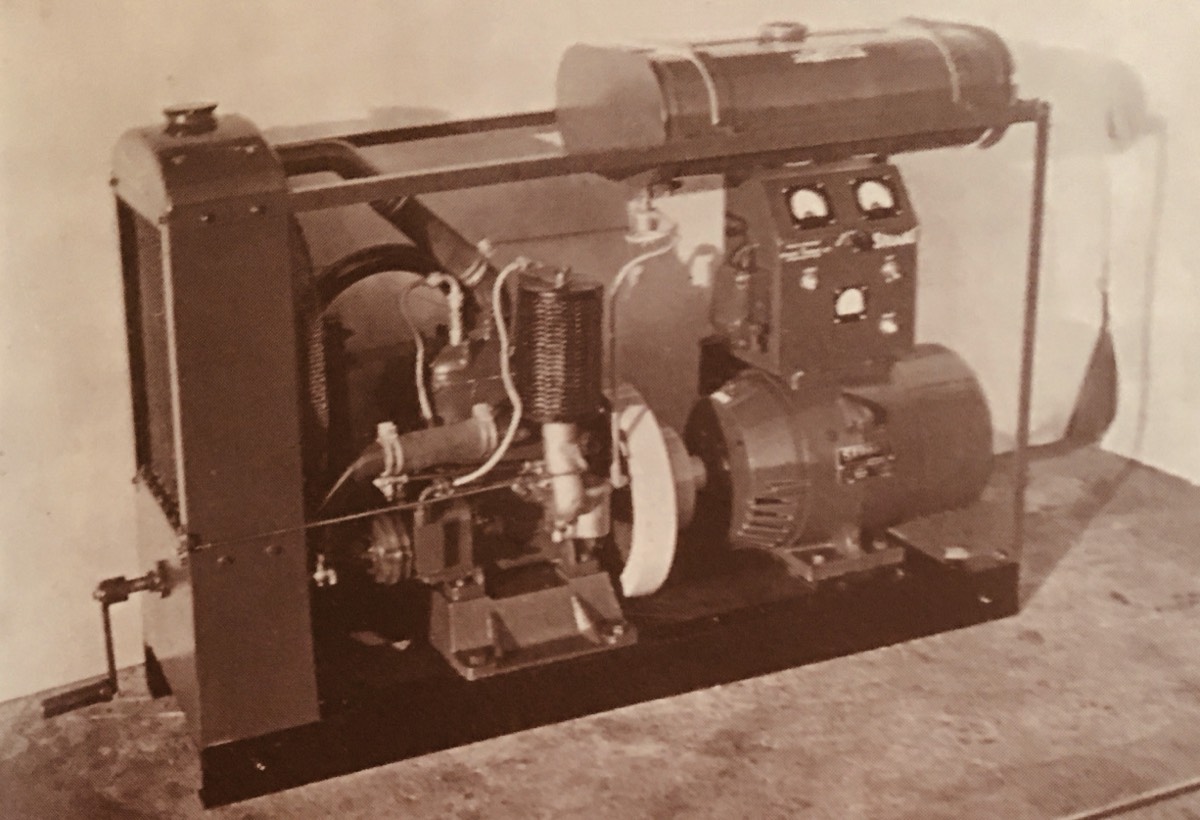

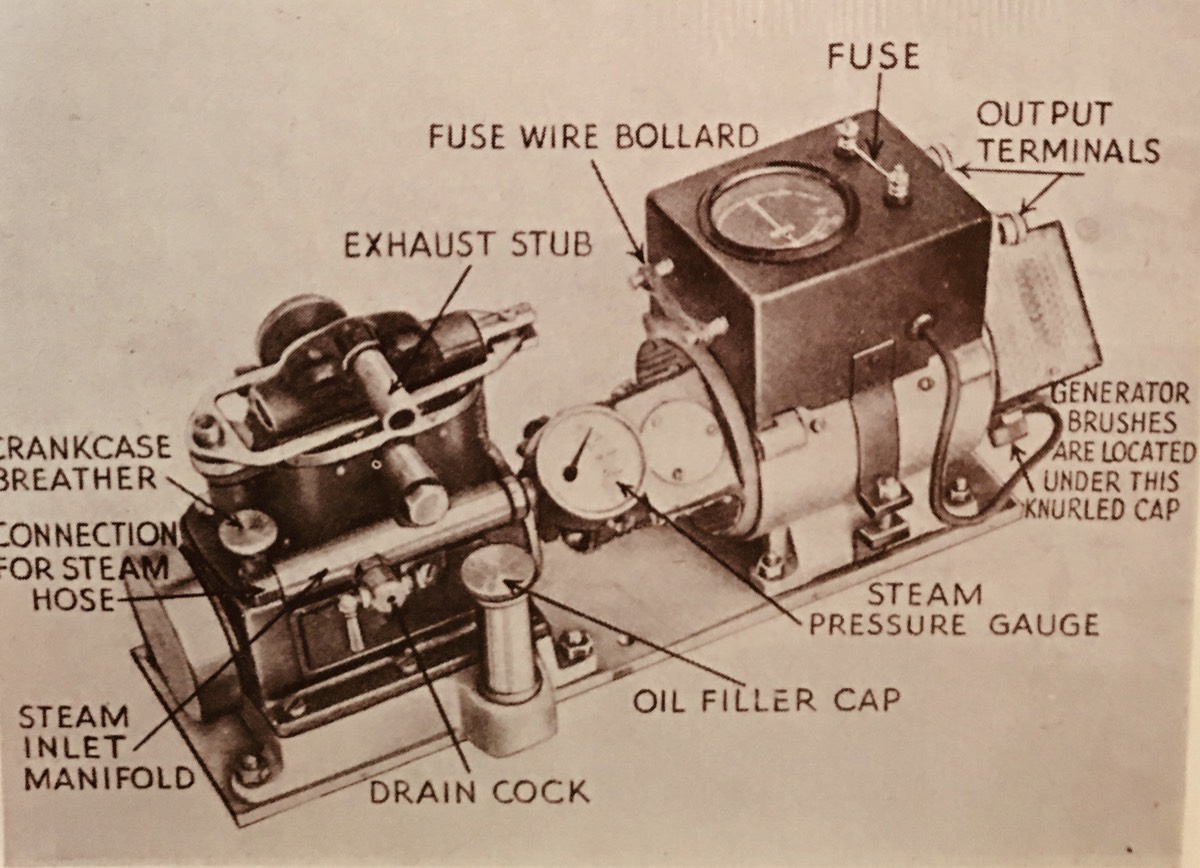

By the beginning of 1939 Stuarts model catalogue contained 72 pages, some twenty-two steam engines were advertised and eight petrol or gas engines. In addition, the firm was making a.fair number of small pumps for garden use and a range of marine petrol engines from 1 to 8 h.p. The war put a stop to the model department as the labour and materials couldn't be justified at that time. However, there was an immediate demand for generating plants and this became the biggest outlet. For instance, many hundreds of the B Class Fairmile motor launches were built during the War, first in this country, and later in naval dockyards overseas and they all carried at least one, if not two, Stuart generating sets. (Fig. 20) The first plant was designed for 110 volt D.C. for anti-submarine detector gear, known as ASDIC. Later on, plants were produced for lighting and battery-charging.

Apart from generating plants, Stuarts did a lot of work for aircraft parts, gun-jacks, turnbuckles and a variety of specialised bits and pieces for the war effort. Like everyone else in those days, the works had to be kept going and at the same time people were expected to help in the Home Guard, the Auxiliary Fire Service, St. John's Ambulance and many other war-time activities. Most people had two jobs and there was the perpetual problem of the "black-out" which proved difficult with the single- storeyed glass-roof workshops at Stuarts. The firm continued to supply marine engines for ships' lifeboats, air-compressors sets for starting purposes, etc.

Probably the most glamorous job was the supply of Stuart 1 1/2 h.p. marine engines for Norwegian dinghies. These boats were used to supply resistance lighters in Norway with food, radios, explosives, etc. (Fig. 21) The dinghies were carried on board conventional fishing craft or sometimes on sub-chasers, then dropped overboard some five or six miles off the Norwegian coast. They were able to go in quietly and sail up the fiords to their secret destinations. Unfortunately, few if any survive as they were regarded as expendable. They were usually sunk on arrival to avoid detection. However, Stuarts have since heard from some enterprising people who have managed to salvage some of the engines and get them going again.

Another important contribution the firm made towards the War effort was the manufacture of 2 Kw. generating plants which could be put down anywhere to provide instant electricity. (Fig. 22) Many hundreds were made and after the War, Stuarts bought back quite a number from army surplus (often in their original packing cases), as they were very good sets and it seemed a shame to see them go to waste. Other smaller generating sets and engines were produced and used for an .incredible variety of jobs, such as powering the pumps on seaplane refuelling launches, on aircraft refuelling bowser lorries, Fig. 23) or supplying power for signals tenders for the Army. (Fig. 24) As well as the larger sets, Stuarts also made some 2 1/4 thousand air-cooled 80 watt sets. The ever- growing importance of Stuart pump production got into its stride about this time and hundreds were made for pumping the bilges of amphibious vehicles and Centurion tanks. A couple of years after the War ended a great blow was shelTered when Alec Plint died rather suddenly. He had been well known in Henley as he was Mayor twice and was also a churchwarden at St. Mary's, Secretary to the Parochial Church Council and on the board of the Charity Trust among many other positions. He was a remarkable man, because with all these interests, he still managed to run the firm very successfully.

After the War there was a tremendous pent-up demand for marine engines, at one time Stuart’s were quoting 12 months' delivery. The London Boat Show started in 1955 and Stuarts found their stand there engendered a lot of business. They were one of the first engine makers to join the Ship and Boatbuilders Federation and Peter Barnard, now Managing Director, was elected as President of the Federation for two years, which was an unusual honour for an engine maker. Though Stuarts made a two-stroke diesel (the HZM), it became too expensive to compete with the mass-produced engines of that time which could be used for other than marine purposes.

To bring Stuarts' history up-to-date, in 1960, Herbert Sanderson, the Managing Director at that time, was knocked down by a car while pushing his bicycle up White Hill and that was the end of his active participation in the firm, though he returned to part-time work some time afterwards. He always took the keenest interest and insisted knowing all the details right up to his death in 1971. He had the uncanny knack of looking at a report and putting his finger on the weak spot you had tried to hide! Mr. William (Bill) Perrin who had become Managing Director after Sander- son's accident, became Chairman of the Company, in 1971. Since the end of the War, the model department had been very slow in getting into its stride again, but this has long been rectified. The main limitation had been in the foundry, not that it was in any way to blame, but it was simply not possible to make a large number of model castings quickly. (Since this talk was given several notable changes have occurred. The petrol engines are no longer made, though spares continue, numerous models and pumping sets have been added to the range, in September of this year the old foundry cupola, which had given so many years faithful service, was supplemented by the most modern electric melting technique. Ed.) Models are nearly always allied with the training of an engineer and there is no finer way of ensuring meticulous attention to detail and accuracy. Stuarts have long had an association with the Training Workshop adjacent to the nearby Technical College and continue to support the various training schemes run by both institutions.

Looking to the years ahead, there is little doubt that precision engineering will continue to fascinate and Stuarts intend to provide the materials and know- how in the model engineering world for the foreseeable future.